The Art of Gathering: Rethinking tradition

It’s time to overhaul our thinking around what a classical music concert should be. We’ve based our traditions on nineteenth century societal hierarchy for far too long.

“When we don’t examine the deeper assumptions behind why we gather,” writes Priya Parker in The Art of Gathering, “We forgo the possibility of creating something memorable, even transformative."

The great paradox of gathering, she says, is that there are so many good reasons for gathering that we often neglect the crucial exercise of establishing the main purpose for coming together.

But isn’t the purpose of a classical music concert to enjoy classical music performed at its highest level? Think again. Classical music is the what, not the why. And when we conflate category with purpose, says Parker, “we end up gathering in ways that don’t serve us.”

Determining why we gather—moving from the what to the why—adds value for everyone involved. And every decision about that gathering, from format and etiquette to audience experience and marketing, becomes easier.

Examining old traditions

When an organization is clear on its reason for gathering, writes Parker, it’s easier to reject old traditions in favor of new ones that, in the case of the arts sector, better serve both the audience and the artist.

But for many of us in the arts sector (perhaps because we often assume our purpose is obvious), the idea of rejecting long-held traditions like concert etiquette feels extremely uncomfortable. And so, with all of the emphasis that classical music organizations have placed on diversity, equity, accessibility, and inclusion since 2020, the very foundation of most classical concert experiences is still rooted in an outdated exclusionary ideal.

Alexander Lee explains on History Today:

Between about 1650 and 1850, opera was ‘enjoyed’ by a relatively broad range of people. Though public opera houses tended to be financed by monarchs, nobles or wealthy merchants, performances were attended by high and low alike.

In the later 19th century, however, the emergence of music halls changed everything. Offering every kind of entertainment—from music to magic—and a deliberately relaxed atmosphere, these quickly won the favour of lower-income groups.

And as opera houses became the preserve of the upper and middle classes, so their audiences attempted to distance themselves consciously from the noisy and often crude behaviour that was increasingly associated with music halls.

Silence, in other words, became what it had never been in the past—a mark of social distinction, of taste and of refinement.

By the 20th century, opera was no longer the 'drawing-room for all society' that it had once been. At least not outside of intermission. Ilana Walder-Beisanz describes it as a shift from the centering of the audience to a centering of the art: “The message was clear: look at the stage, not each other. Pay attention to the music and the action. Let the artists control your experience.”

Here’s the thing: Rituals emerge to solve a specific challenge. And when rituals and traditions align with the purpose and needs of the group, they can be powerful. They promote a sense of belonging, create efficiency, minimize risk. “When like gathers with like, etiquette often does its work so well that no one notices its presence,” writes Priya Parker. But when they are solving for an outdated purpose in a changed world, Parker cautions, traditions can become a handicap.

And there’s no denying that the 21st century world has changed. The United States’s dramatic demographic shift is just one example. In 1990, just 19% of the population was non-white. In 2014, less than 25 years later, Indigenous, Black and People of Color represented 43% of the population. Our definition of diversity has broadened to include sexual orientation. The middle class, according to the Pew Research Center, has contracted over the past five decades from 61% of the population to 50%. Then there’s technology. And COVID-19. And climate change.

With the rapid audience decline that began in the late 20th century (down nearly 50% since 1997), classical music organizations have tried to eradicate the perception that their world is welcoming only to the upper crust. Yet the art-centering, reverential expectations for concert etiquette that became ritualized by high society in the late 19th century remain largely unchanged today. And negative attitude affinities, says Colleen Dilenschneider, are still growing—now at 48.2%.

Why does nearly half of the U.S. population feel unwelcome in the world of classical music? Consider how an Outsider feels when stepping into an unfamiliar world; into a culture not their own. What is their experience of this new world? Parker explains it this way:

“The etiquette approach to life is imperious. It is the opposite of humble. It shows minimal interest in how different cultures or regions do things. It upholds a gold standard of behavior as the only acceptable one for people who wish to be seen as refined. It is not interested in variety or diversity.”

In essence, Parker says, implicit rules marginalize those who aren’t familiar with them. So does traditional concert etiquette promote inequality and discourage diversity? Should we toss out etiquette altogether and return to the raucous audiences of the 18th-century opera house, where the purpose for gathering was entirely social?

I’m not advocating for a free-for-all. As a former opera singer, I know how demoralized I would feel to be drowned out by the clinking of sorbet spoons. But how do we maintain a respect for the performers—and recreate some of the magnetic vibrancy of that 18th century opera house—while also creating a more inclusive experience?

Creating new traditions

In response to today’s increasingly more diverse society, Parker recommends the creation of what she calls pop-up rules. Being explicit about the rules of your gathering can override unspoken norms. While implicit etiquette defines behavioral expectations for homogeneous groups, explicit rules help diverse groups gather, because they help provide clarity on expectations and lead to greater psychological safety.

Consider the anxieties an Outsider might have about the classical music experience:

What if I clap at the wrong time?

What if I don’t own a tux?

How long will the concert be?

What am I supposed to do while the orchestra plays?

What if I have to use the restroom? What if I have to cough?

Do I really have to turn off my phone and sit in the dark for two hours? What if my babysitter has a question?

Rejecting class-specific, implied traditions in favor of gathering-specific rules cultivates a new freedom and openness for everyone. It provides the opportunity to temporarily equalize all attendees.

Pop-up rules say “All are welcome. We do things differently here, because we recognize that each patron is unique. If you’re new, you can relax. If you’re a regular, try something new and experience this art form in a new way.”

What new rules can we establish to eliminate the Outsider’s anxiety and help them not feel less than? In what ways can we acknowledge the dramatic changes our world has undergone since the 19th century? Since 2019?

Pop-up rules in action

The California Symphony tells their audiences: “Phones are allowed (on silent). Clap when you like what you hear. And wear whatever makes you feel comfortable.” Executive Director Aubrey Bergauer reported that while there initially were concerns that these changes might disgruntle their Insiders, “The response has been overwhelmingly positive… Musicians and longtime patrons say, ‘I look around the hall and see it’s packed now when it used to be half empty. I see there are younger people here and I feel a different energy than I’ve ever felt before.’”

Jocelyn Lightfoot of the London Chamber Orchestra writes, “By insisting our musicians wear a specific western-influenced and gendered dress code, we as an orchestra created a boundary between ‘us’…and ‘them’; the audience, who ideally come from all social classes, financial backgrounds and include all gender identities and cultures.” Now, the musicians of the LCO are encouraged to choose concert attire that better reflects their individual identities. And the LCO encourages their audiences to reciprocate. “It is crucial that we mirror the community that joins us at our live events and the beautiful variety of people that includes…This way we can celebrate, together as equals, the absolute joy of music making which grows from diverse individuals’ lives and experiences.”

Bourby Webster of the Perth Symphony Orchestra, whose mission is “Music is for everyone,” shared their approach to cell phones on LinkedIn: “At the start of all Perth Symphony’s concerts we have a ‘voice of god’ recording asking patrons to get out their phones and start filming the bits they love. Draws a laugh every time, as they’re expecting to be told to put them away. Of course, we ask them to silence their phones, and also ask to ensure they don’t disturb those around them by filming too long. We often make this request using the voice of the performer or artist.”

Drew McManus reported on his blog: “At a recent [Lakeview Orchestra] concert, I was pleasantly surprised to hear that the orchestra was encouraging patrons to use their phone to take no-flash pics, but only if they were sitting in the last five rows of the main floor or balcony.” Lakeview’s website says: “You are welcome to use your mobile device on silent during Lakeview Orchestra performances while seated in the Phone Zone. The Phone Zone is located in the upper balcony and rear main floor (under the overhang) so as not to disturb other patrons with excess light from your device. Please share photos and video of the performance using #lakevieworchestra and @ us on Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter.” Holly Mulcahy shared the concert signage (right) on Facebook.

I’ll be the first to admit that the cell phone issue is a tricky one (the trickiest?), and there’s no one way to address it that works for every organization. But it’s encouraging to see some groups experimenting with a shift away from tradition. Elevate Ensemble is another great example.

Reinventing the format

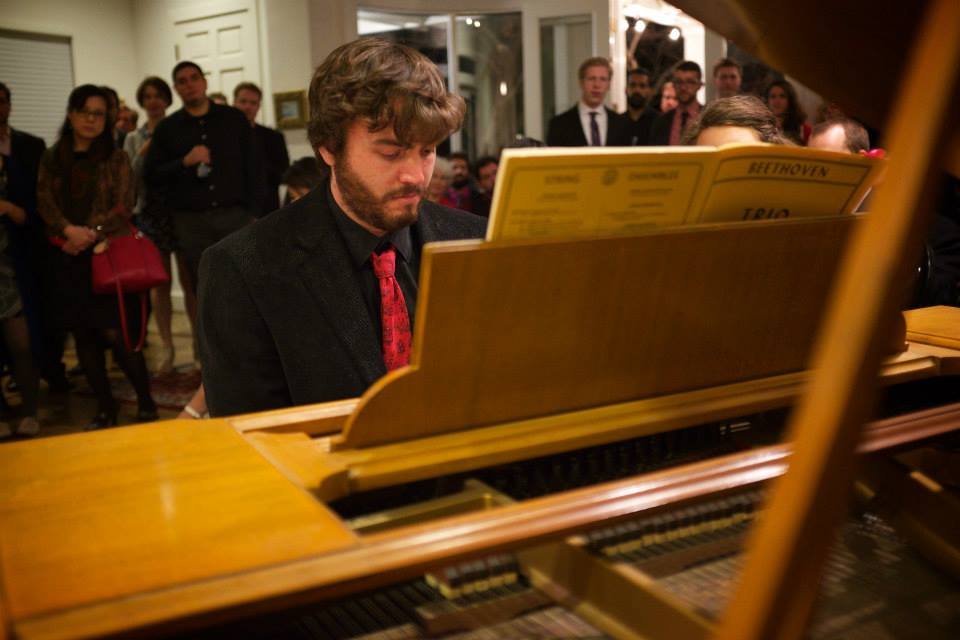

Conductor Chad Goodman has taken the entire audience experience and completely reimagined it. In 2014 he founded Elevate Ensemble, a San Francisco-based “pop-up orchestra” that performs in unorthodox venues: yoga studios, historic homes, art studios, warehouses, and more. Goodman’s goal: Give people the opportunity to experience live performances of classical music—but in a way that is welcoming and inclusive to Outsiders.

“We collaborate with other local artists, including poets, chefs and photographers,” says Goodman. “Some…show up…for the poet or chef, others to support the music, but everyone leaves with a new, shared appreciation for the…creative arts scene we have in San Francisco.”

Elevate events were known to blur the line between concert and party. Goodman describes one event where guests enjoyed food prepared by a local rising chef. Short music sets paired underrated gems from composers of the past alongside new works from local composers. Between each set was an intermission which provided ample time for the audience to interact with each other and the performers, while enjoying the chef’s next offering of food and drink.

In addition to making the concert format more accessible, Goodman has always been a strong advocate for commissioning and promoting new works. Why? “We need our audiences to realize that there are people out there just like them, who happen to be expressing their experiences of the present day through music.” He found that the chance to experience a world-premiere created a different kind of energy and excitement in the audience, who were invited to learn from the composer about what inspired the piece and what the compositional process was like.

Goodman knew he was onto something when Elevate began to build a loyal fanbase mostly comprised of millennials, with an average attendance of about 100 (but sometimes up to 200, depending on the capacity of the venue.)

The best part? “Many of these people were coming up to me after shows and saying that until now, they had never thought that classical music was for them.”

Arts patrons are often left to fend for themselves when it comes to interacting with the art and with their fellow attendees. But 'chill hosting', warns Priya Parker, isn’t welcoming, and it doesn’t cultivate a meaningful experience that keeps them coming back. So how can arts organizations be better hosts?